history

PAckers

Birth of a Team and a Legend

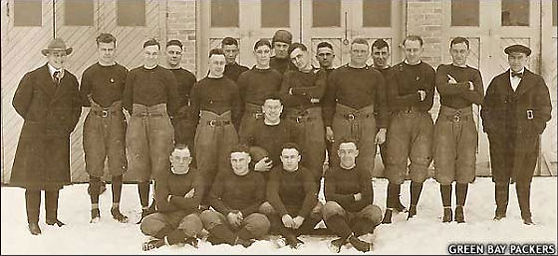

The Green Bay Packers, arguably the most storied franchise in the National Football League, were organized on Aug. 11, 1919, in the dingy second-floor editorial rooms of the old Green Bay Press-Gazette building, located on Cherry Street in downtown Green Bay.

Never imagining what might become of the semipro football team being formed that day, nobody documented who was there or how many were on hand. There had been no announcement of the meeting beforehand, and the Press-Gazette provided no details about it the day after.

Whether a full complement of players attended or if it was simply a small gathering of the team’s prime movers was never made clear. Nor was it spelled out if much of the preliminary work had been completed beforehand or if the meeting itself triggered a rapid-fire chain of events.

John Calhoun

Whatever the case, the Press-Gazette in its Aug. 13 edition revealed that the Indian Packing Co. would sponsor the team and referred to it for the first time as the “Packers.” The paper said home games would be played at Hagemeister Park; listed 38 prospective candidates for the team, mostly former standouts at Green Bay East and West high schools; and noted full uniforms would be provided to up to 20 players.

“It will be the strongest aggregation of pigskin chasers that has ever been gathered together in this city,” the Press-Gazette proclaimed.

A second meeting was held at the Press-Gazette on Aug. 14, three days after the initial one, and nearly 25 players were in attendance. Curly Lambeau was elected captain of the team, and George Whitney Calhoun was named manager.

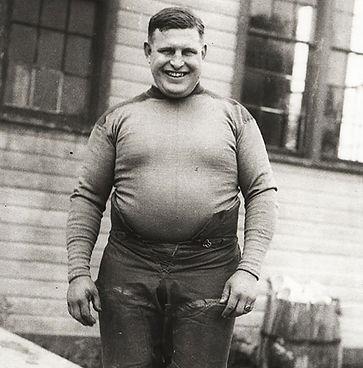

Lambeau was a former star at East High School and played on Coach Knute Rockne’s first team at the University of Notre Dame in 1918. Back home after dropping out of school in December, Lambeau was working for Indian Packing at the time. Calhoun, great-grandson of Daniel Whitney, founder of the city of Green Bay, was an editor at the Press-Gazette.

The story handed down for decades was that the impetus for the initial meeting was a chance encounter at a downtown street corner between Lambeau and Calhoun. In his 1985 book about the history of the Packers, longtime executive committee member and onetime Calhoun colleague John Torinus changed the setting to a conversation over a glass of beer.

Whether it’s mostly urban legend or if there’s a true story in there somewhere will remain a mystery for the ages. Too much time has passed. But Lambeau and Calhoun have long been regarded as the Packers’ co-founders and there’s little or no evidence to dispute that.

The Packers again played an independent schedule against mostly neighboring towns the next year and again dominated the competition, finishing 9-1-1.

The first season, the Packers won 10 games and lost one against opponents representing mostly nearby towns in northeastern Wisconsin and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

The team conducted most of its practices that first year on a field next to the Indian Packing plant at the end of Morrow Street, but it played its eight home games at Hagemeister Park on an open field with no fence or bleachers. Calhoun “passed a hat,” as did others, to collect spare change and help cover expenses.

C.M. “Neil” Murphy, a local typewriter salesman, was named business manager in July and organized a committee to build a fence around the Hagemeister playing field so the Packers could charge admission.

Thanks to the support of Indian Packing, the local Association of Commerce, local contractor Ludolf Hansen and fans who provided volunteer labor, construction of the fence began in late August and was completed before the first game in late September.

Curly Lambeau

Better yet, their financial outlook improved considerably.

By mid-October, two large sections of bleachers were erected so fans would no longer have to stand along the sidelines to follow the action.

JOINING THE NFL

UNIFORMS

P A C K E R S

GREEN BAY

the original

the original

GREEN BAY

1919

P A C K E R S

On Aug. 27, 1921, the year-old American Professional Football Association awarded a franchise to the Acme Packers of Green Bay during a league meeting in Chicago. The Acme Packing Co., based in Chicago, had purchased Indian Packing eight months earlier. Less than a year later, the APFA would change its name to the National Football League.

Green Bay was now in the big leagues – sort of.

Most of the APFA’s 21 members that second year were located in small hotbeds of football rather than big cities – places like Canton, Ohio, Hammond, Ind., and Rock Island, Ill.

Then again, compared to Green Bay, maybe those were big cities.

Green Bay was the smallest city in the league when it joined in 1921 if you discount a minor technicality – Tonawanda, N.Y., was smaller but its team lasted one game and played on the road – and has been ever since, except for a brief period in the late 1920s.

Green Bay’s population was 31,017 based on the 1920 U.S. Census. Not only was it the smallest city in the league, it was smaller than six other cities in Wisconsin, including Superior and Oshkosh.

No doubt to those who lived through it and also through the lens of history, it’s almost incomprehensible that the Packers survived. They’re closing in on their 100th anniversary, but until they were nudging toward 50 they were perpetually on their deathbed.

Take their first league season, for example.

The Packers pulled off a major coup when they signed lineman Howard “Cub” Buck, a veteran of the famous Canton Bulldogs. They won their inaugural league game against the Minneapolis Marines on Oct. 23, 1921. They were able to book games with the formidable Chicago Staleys (Bears) and Chicago Cardinals. And they finished with a winning record, 3-2-1.

Howard "Cub" Buck

But then scandal nearly doomed all that they had accomplished. On Dec. 4, 1921, in a non-league game against Racine billed as a battle for the state championship, the Packers used three Notre Dame players, with college eligibility remaining, under assumed names and got caught. Less than two months later, Green Bay was booted from the league – albeit not for long.

Thanks to Lambeau’s persistence and the impression Green Bay had made on other club owners during its first season, the Packers were reinstated at the next meeting in June.

The Acme Packing Co. bowed out of the picture at that point, after just one season, and a small group organized as the Green Bay Football Club and headed by Lambeau and Calhoun took control of the franchise.

Plagued by limited resources and terrible weather, the new owners barely survived their first season.

A game against Columbus in early November was played in a driving rain and resulted in a loss of $1,500 when the total rainfall for the day fell three one-hundredths of an inch short of the amount needed for the Packers to collect on their rain insurance. On Thanksgiving, a 12-hour rainfall ruined what was supposed to be Booster Day, contributing to a sparse crowd for a non-league game against Duluth and another financial disaster.

Club officials nearly canceled the game, but were persuaded to play by Andrew Turnbull, one of the owners of the Press-Gazette.

Nearly 25 years later in a three-part series, Calhoun wrote that Nov. 30, 1922, “marked a turning point in the history of the Packers.” He said Turnbull promised that if club officials went ahead and played their game that day, he would get Green Bay’s business community to rally behind the team once the season ended.

True to his word, Turnbull led the effort to create the nonprofit Green Bay Football Corporation before the start of the next season. The Packers were now a community-owned team. Their investors were their fans.

Super Bowl Seasons

Super Bowl I, 1967

On January 15, 1967 the Green Bay Packers defeated the Kansas City Chief 35 - 10 to win Super Bowl I. The game was played at Lost Angeles Memorial Stadium infront of a crowd of 61,946 fans. The Packers were led to victory by ledgendary coach, Vince Lombardi and MVP quarterback, Bart Starr.

At halftime the Chiefs were only trailing by four, however the the Packers dominated the second half. The Packers offense scored another 21 points in the second half, while their defense shutout the Chiefs.

Super Bowl II, 1968

On January 14, 1968 the Green Bay Packers defeated the Oakland Raiders 33-14 to win Super Bowl II. The game was played at the Orangle Bowl in Miami, Florida infront of a crowd of 75,546 fans. The Packers were led to victory by ledgendary coach, Vince Lombardi and MVP quarterback, Bart Starr.

The Packers scored 16 points in the first half, while holding the Raiders to a touchdown. The second half was much of the same with the Packers scoring 17 more points and the Raiders 7. Being the overwhelming favorite, the Packers defeated the Oakland Raiders quite easily.

Super Bowl XXXI, 1997

On January 26, 1997 the Green Bay Packers defeated the New England Patriots 35-21 to win Super Bowl XXXI. The game was played at the Louisiana Superdome in New Orleans, Louisiana infront of a crowd of 72,301 fans.

Both teams scored a combined 42 points in the first quarter, the most is Super Bowl history. In the 3rd quarter, the Patriots cut the lead to 27–21 off of running back Curtis Martin's 18-yard rushing touchdown. But on the ensuing kickoff, Desmond Howard returned the ball a then-Super Bowl record 99 yards for a touchdown. The score proved to be the last one, as both defenses took over the rest of the game.

Super Bowl XIV, 2011